To date TSBNZ has spent a fair bit of time looking at level crossing safety. Along the way one of the learnings has been the apparent extent to which the agencies concerned are operating their own systems for managing level crossing safety in isolation from each other and blaming the other for safety problems. The parent agencies concerned are, of course, Kiwirail and Waka Kotahi. Kiwirail’s position is that they would like to close crossings and would close as many as they could, without much consideration about the needs of the communities they are in. Kiwirail has a sinking lid policy for level crossings in general, whereby they are actively pushing to have the total number reduced, and no new ones to be opened, if at all possible, unless new safer ones are replacing older dangerous ones. There are pros and cons to this approach, of course. On the one hand, there are plenty of situations where level crossings are quite close together where the justification for keeping crossings open is weak. Think about the scenario in an average town or city where streets are a few hundred metres apart and where people insist there has to be a level crossing on every street, no matter how few people may actually be using it. On the other hand, in rural areas, crossings may be kilometres apart and that distance be a real challenge for communities, like the way that major rivers have few bridges.

Waka Kotahi, on the other hand, seems to view crossings as a necessary evil, but it simply tries to ignore them as much as possible. This leads to strange perverse outcomes. A first example of this is at Mackays Crossing just north of Paekakariki. There has been a level crossing there perhaps “forever”, or ever since the Wellington and Manawatu Railway pushed their line through in the 1880s.

After many years of representation and advocacy for the crossing to be eliminated, in 2005 State Highway 1 was rerouted to cross the line via a new overbridge. The crossing wasn’t removed, however, and remains in use today as part of an interchange for traffic entering and exiting the Kapiti Expressway. In 2022, the interchange became the northern terminus of the Transmission Gully motorway. Why this is a ridiculous and utterly unjustifiable extravagance is that there are not one but two other interchanges in close proximity, with one at Paraparaumu about 3 km further north and another at Paekakariki only 2 km south. The Mackays Interchange only serves the Queen Elizabeth 2 Park in the main, and considering the short distance to other interchanges, the original plan to have no interchange there should have prevailed and allowed this crossing to be completely closed. A similar issue is seen at Rolleston where on Hoskyns Road there have been many near misses at a level crossing that carries a high volume of traffic entering and exiting State Highway 1. WK proposes now to build an overbridge to allow the people of Rolleston to cross over SH1 and the Main South Line to enter the industrial area on the other side, from where they can cross back over the railway on the level via the existing crossing which will be retained as part of a new onramp to the highway. Once again, expediency triumphs over common sense.

A second example of a strange way of dealing with a railway crossing in a roading context is seen in Blenheim where one of the country’s four “railway roundabouts” was built around two decades ago. The exact date is uncertain, but TSBNZ suggests it was probably done as a part of a larger roading project around 1999 or 2000 that diverted the main highway SH1 about a hundred meters to the east. To make room for this realignment, the railway line also had to be moved and the Blenheim station building was relocated. This was obviously a cheaper solution to relocating the highway to the outskirts of the town, a preferable safety alternative.

As it transpires, after twenty years the people of Blenheim have had enough of their special roundabout and they want it gone. As noted there is a second smaller roundabout of this type at Ahuriri (Napier) (a slightly different design with the railway going through through one of the approaches) and a third at Kumara Junction where SH73 and SH6 meet (railway through the centre of a smaller single lane roundabout). A fourth, and the most recent, was constructed at Arahura, just a bit south of Kumara, in conjunction with the replacement of the combined bridge there, being quite similar to the third example. There is no real logic for being able to understand why Waka Kotahi considers these structures necessary, but on the grounds purely of economic expediency, they have dealt with a major issue that is found with many level crossings around New Zealand that have been found to exhibit significant danger for unwary motorists, when a busy intersection is placed too close to a railway crossing. Since in most such instances the risks are due to a lack of traffic control on the intersection approach crossing the railway, one can see a certain perverse logic in bringing the railway wholly within the orbit of the semi-controlled roundabout. However, there are numerous other intersections in NZ where traffic lights are interlinked with railway crossing signals to control vehicle flows over an adjacent level crossing, and the only reason any of these roundabouts really are necessary is to avoid installation of traffic lights, which is illogical considering Kiwirail requires warning signals and/or barrier arms to make the crossings as safe as possible given the inherent risks of having the track going through a road intersection.

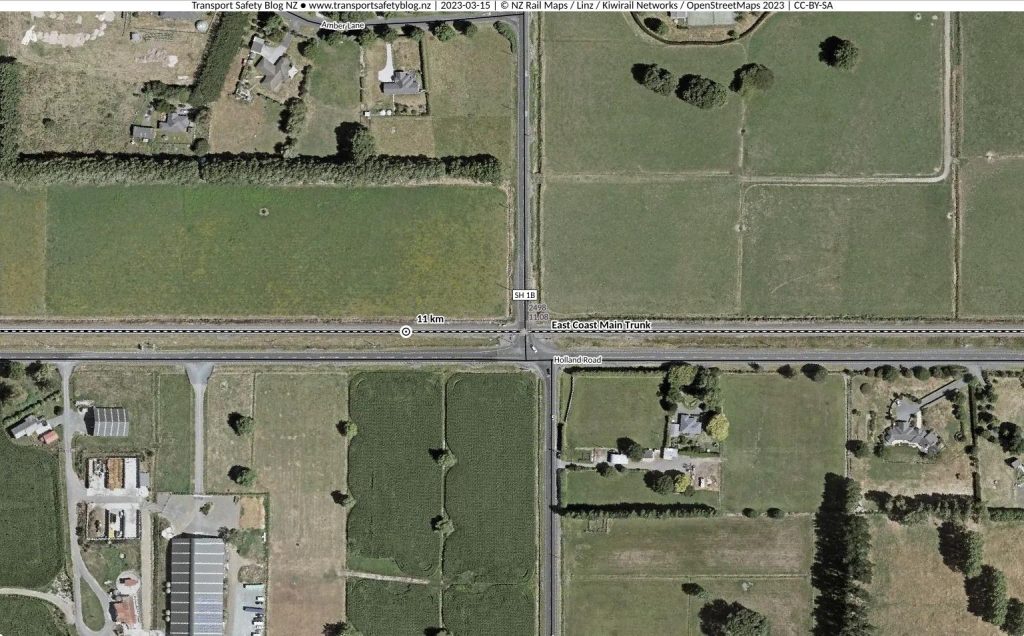

Third example for today is Telephone Road level crossing near Puketaha.

Telephone Road has had a level crossing serving the local community for more than 60 years from what TSBNZ can determine. Around the year 2000, Waka Kotahi took over management of the road from Waikato District Council and changed its designation to State Highway 1B, a convenient bypass for traffic on State Highway 1 to avoid Hamilton City, which is 11 km to the west. Safety issues at this location include that the level crossing is humped, which means long or low vehicles have grounded on it from time to time, and that the adjacent intersection with Holland Road is dangerous – partly because of its odd asymmetric layout and partly because of uncontrolled traffic flows. A proper safety assessment for the crossing would also address the risk for right turning vehicles from Holland Road heading north to overshoot the crossing due to inadequate separation, whilst short stacking is already recognised. Therefore, for many years, this crossing has ticked a number of high hazard boxes, and in public statements recently Kiwirail has called it “one of the most dangerous in the country”. But for its part, Waka Kotahi has spent all of the 23 years it has managed this road avoiding any possible safety improvements to it – until last year when the new Waikato Expressway opened and took much of the traffic. WK then presented its proposal to close the crossing completely to the outrage of the local community. Since then WK has backpedaled somewhat but is still insisting there is no money available to fix the issues. In this rural locality, the next nearest crossing is 4 km further east at Eureka, so in the worst case scenario, a trip from one side to the other could involve an additional 10-15 km of travel. (Since TSB first started looking into this issue a few weeks ago, WK and other agencies have released a new update on the Telephone Road crossing project, this will be the subject of a separate blog post in the near future)

The government agency’s intransigence when it comes to fixing dangerous road layouts around level crossings trickles down into local council roads, where many similar problems are common, and Kiwirail can do very little about them, except by upgrading crossing signals. In TSB’s estimation, level crossing safety issues are probably about 5% able to be addressed by Kiwirail and about 95% needing to be addressed by roading authorities. The fact that they are not being addressed, or only very slowly, and that Kiwirail’s safety assessment process does not fully evaluate risky road design, is what motivates TSB to look for a method of integrated safety assessments. Waka Kotahi and Kiwirail are currently working on several projects of level crossing improvements around NZ, and a major one is in the Wairarapa where some 30 crossings are slated for removal, along with the closure of others. The Wairarapa project provides an interesting opportunity to evaluate WK’s approach to crossing safety improvements and TSB is currently requesting details of specific safety treatments from agencies. This in turn will form a good basis for creating some initial ISAs just to get this idea rolling.